Fermentation isn’t magic, but it can sure feel that way when you watch the bubbling airlock on a carboy crank up and slow down over a stretch of days. Still, every home brewer hits the same impatient wall: is two weeks long enough to ferment beer? While plenty of recipes promise fizzy drinkability in two weeks, you might want to pause before bottling that batch so soon. Cutting corners could mean explosive bottles, weird flavors, or flat-out disappointment. The truth? It’s a bit more complicated than the numbers printed on your yeast packet.

The Science Behind Beer Fermentation Timing

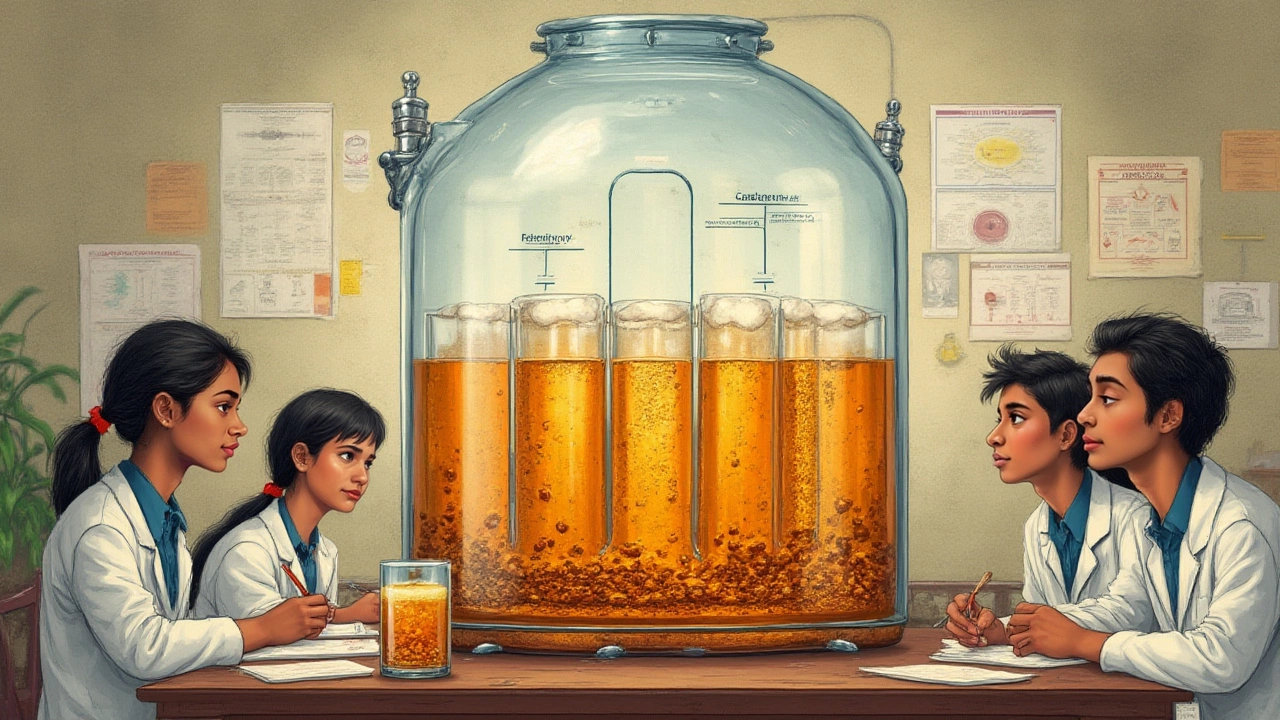

Fermenting beer isn’t just about watching bubbles and hoping for the best. It’s a careful dance of biology, chemistry, and, yes, a bit of human patience. When you pitch yeast into your wort (the sweet liquid extract from grains), those tiny fungi get right to work. Within hours, they chow down on sugars, multiply, and start pumping out alcohol and carbon dioxide. This lively first act is called ‘primary fermentation’ and, in most homebrewing experiences, wraps up its most visible action within 4 to 7 days. The airlock activity slows, and it’s tempting to think the job is done.

The reality? While the vigor ends early, yeast keeps working even after the bubbles fade. Those last few days to a week are when yeast clean up byproducts like diacetyl (think warm butter), acetaldehyde (think green apples), and sulfur notes that aren’t exactly welcome in your pint. If you rush the process, these off-flavors might sneak into your final beer. Yes, most standard ales (like pale ales or porters) can hit their stride with two weeks in the fermenter if you’re using healthy yeast, a steady temperature (around 18–22°C or 64–72°F for ales), and moderate gravity wort (OG under 1.050). But lagers, high-ABV brews, or anything with lots of hops or specialty grains usually need more time.

Then there’s the issue of yeast flocculation—the process where yeast cells clump up and settle to the bottom. This happens more slowly as the last sugars are mopped up. Leave your beer longer, and it’ll clarify naturally. Rushing it? You could wind up with hazy, overly yeasty brews that taste muddy or unfinished. Want another reason to wait? Some residual fermentation can still be happening even if it’s nearly invisible. If you bottle too soon, trapped sugars might kick off renewed fermentation in the bottle—leading to excessive carbonation or, in rare cases, dangerous bottle bombs.

Different styles, different waits. Standard American pale ales might be ready to bottle after 10–14 days. An imperial stout, which starts with higher gravity, could need three to four weeks. Belgian ales, sour beers, and anything wild or funky could take a month or more; some lambic brewers let their creations rest for years! Hefeweizens are an exception—drink them fresh for signature fruity and clove notes, but be careful not to bottle prematurely.

Modern yeast strains are pretty robust, and with the right temperature control and proper sanitation, two weeks is possible for a satisfying brew. But ‘possible’ isn’t always ‘best.’ Even commercial brewers—who have every incentive to move beer swiftly—often give their products some conditioning time after primary fermentation. If you ever glad-handed a brewery tour guide, you’ve likely heard of “cold crashing,” allowing beer to chill, drop out any leftover gunk, and smooth out flavors, an extra step that homebrewers with a fridge can mimic at home.

The final secret? A hydrometer. These floaty little gadgets measure specific gravity, which tells you if the sugars have been fully fermented. If you get the same reading for three days running, fermentation is done. Don’t believe the airlock—trust the hydrometer. It’ll save you from premature bottling regrets, sticky bottle explosions, or sad, half-finished beer.

What Happens if You Bottle Too Early?

This is where things get messy—sometimes literally. Bottling before fermentation is truly finished is the most common cause of over-carbonation and, at worst, glass-shattering bottle bombs. Even a small percentage of residual sugar can give surviving yeast the fuel to keep munching away inside sealed bottles. The resulting carbon dioxide builds up and, without anywhere to go, the pressure makes bottles gush foam or worse, shatter. Not exactly the homemade surprise you want to hand your friends at a barbecue.

But even if you avoid the fireworks, young beer is almost always a letdown in taste. Unfinished fermentation often leaves “green” flavors behind. Take diacetyl—brewers will spot its buttery slickness instantly, and it comes from yeast not getting the time they need for a clean-up phase. Same goes for acetaldehyde, which brings out off-putting, almost cider-like crispness. These flavors fade as yeast finish their job, given the time. Without that break, your hard work might only leave you with disappointment and a batch you’re embarrassed to share.

Another point: clarity. Freshly fermented beer can look cloudy with tons of floating yeast, proteins, and hop debris still swirling around. While certain styles like New England IPAs are deliberately hazy, most homebrewers don’t want muddy-looking pales or stouts. Give the brew an extra week—things settle, and your beer pours clear.

Plus, premature bottling risks inconsistent carbonation. With active yeast and residual sugar, bottles from the same batch can carbonate at wildly different rates. Some might shoot foam as soon as you pop the cap, others might be flat as pond water. Consistent priming and a fully fermented base beer are the only way to sidestep this mess.

Modern yeast strains are generally reliable and often finish up in less than two weeks, but homebrew setups vary a lot. Maybe your batch is in a cool basement and needs a few more days, or perhaps you used a higher-gravity recipe that just takes longer. People brewing with wild yeasts, extra-hoppy ingredients, or high-ABV kits should expect to double the normal waiting time for best results. If you absolutely have to speed things along, you can try fining agents or cold crashing to help clarify faster, but nothing beats simple patience. Experience shows that a one-week difference in fermentation temperature or resting time can make night-and-day differences in taste, clarity, and even head retention.

Here’s a quick sense-check before bottling:

- Check the gravity three days in a row. No movement? You’re ready.

- No visible bubbling for several days? Good sign, but always check with a hydrometer.

- Beer tastes clean and not green or buttery? You’re probably there.

- Doesn’t smell like rotten eggs or apples? Perfect.

For anyone brewing their first batch ever, here’s a tip: treat beers with patience and suspicion. If you’re not sure, it’s better to wait an extra week than rush it. If the batch doesn’t taste quite right after bottling, self-control can win out. Leave a few bottles for a month or two—sometimes age alone mellows harsh flavors and brings surprising complexity. Real stories from homebrewers backed by decades of forums and competitions show that two weeks is almost always the bare minimum for ordinary ales, and seldom enough for lagers, high-gravity drinks, or big, hoppy beers.

Making the Most of Fermentation: Tips for Better Beer

If you’re aiming for the best-tasting homebrew, a few simple tricks can help you get more from each batch, whether it’s your first or fiftieth. Start by picking a yeast strain that matches your style—don’t just grab the generic dry yeast that comes with every kit. For most ales, strains like US-05 (clean American), Nottingham (UK), or WY1056 (classic West Coast) will churn through ordinary wort in two weeks or less, especially if pitched at the right cell count and kept around 20°C/68°F. For lagers and Belgians, specialized yeasts and an extra week or two really help tease out character and drop unwanted byproducts.

Temperature control matters more than you might think. A few degrees too hot, and yeast can throw off unpleasant fusel alcohols (solvent-like or nearly plastic notes). Too cold, and they’ll sulk and slow fermentation. Using a dedicated fermentation fridge or a temperature-controlled wrap can stabilize your batch and deliver repeatable results. Regularly record temperatures, and resist the urge to move your fermenter to a warmer spot early to speed up the process—fast changes can shock the yeast and create stalling or off-flavors.

Sanitation is second only to patience. Every carboy, bucket, hose, or bottling wand should get a fresh rinse with no-rinse sanitizer like Star San or Iodophor. Even a napkin with wild bacteria can spoil a batch in ways that time can’t fix. Develop a simple cleaning routine, and never skip a step, even if you’re tired and tempted. Your future beer will thank you.

Don’t forget finishing touches. Cold crashing (chilling the fermenter to just above freezing) for 24–48 hours before bottling drops out suspended yeast and bits, making for a clearer pour. If clarity is important, add finings such as gelatin or isinglass for an easy lift. Some brewers experiment with wood, fruit, or spices after active fermentation, adding a secondary step for big flavor, but always follow with a gravity check and extra time to ensure fermentation’s really done.

If you really want to geek out, consider experimenting with split batches: bottle half at two weeks, the rest one week later, then batch-taste. Most brewers quickly discover that their patience pays off. Side-by-side tastings show beers conditioned for three to four weeks polish out rough edges—bitterness, harshness, and haze fade, while flavors blend and mature. For some, the difference can be huge, especially in complex styles or high-hop brews like IPAs, where hop burn lessens with 7–14 extra days.

And don’t be afraid to keep notes. It’s the only way to improve from one brew to the next. Log starting and final gravities, fermentation temperatures, dates, and tasting notes. Over time, your own data becomes more trustworthy than that random guy on an internet forum.

Last but not least: avoid the myth that quicker is always better. Some commercial craft beers do hit shelves in just two weeks, but they use pressurized fermenters, centrifuges, and dedicated QA labs. Your homebrew setup, as fun and satisfying as it is, relies on gravity, simple yeast, and kitchen science. Give your beer time to finish its journey, and you’ll tap into deeper, fuller flavors—the kind that have made homebrewing such an addictive, rewarding hobby for centuries.

You might see quick, drinkable results in two weeks if you pick the right recipe, maintain flawless sanitation, and have stable fermentation temperatures. But if you want a truly great ferment beer result—one that makes friends pause and say “wait, you brewed this?,” don’t rush what nature already has perfectly timed. The proof is in the pint, and sometimes, in the patience.

Categories